THE TRUTH ABOUT freud

From the Freud archives to #MeToo

In 1980, the Freudian psychoanalyst, Jeffrey Masson, obtained from Anna Freud, the daughter of Sigmund Freud, the authorization to publish all the letters sent by her father to his friend Wilhelm Fliess. Indeed, only half of these had been revealed to the public, the others having been sequestered for 50 years, at the request of Anna Freud, in the archives of the Library of Congress in Washington.

In 1980, the Freudian psychoanalyst, Jeffrey Masson, obtained from Anna Freud, the daughter of Sigmund Freud, the authorization to publish all the letters sent by her father to his friend Wilhelm Fliess. Indeed, only half of these had been revealed to the public, the others having been sequestered for 50 years, at the request of Anna Freud, in the archives of the Library of Congress in Washington.

Jeffrey Masson discovers that the letters that have remained secret deal in particular with Freud's discovery of the theory of seduction and the circumstances that led him to abandon it for the theory of drives. A very embarrassing secret that his heirs wanted to keep for at least 50 years, buried in the archives of Congress... This renunciation had serious harmful psychological consequences for people treated in psychoanalysis, because it contributed to fueling sexual violence against women. women, while making them feel guilty.

Thanks to #MeToo who, a century later, is helping to overcome the curse of abandoning the theory of seduction for the theory of drives.

This film features the exclusive historic interview with Jeffrey Masson that revealed the secret…

This film was directed by Michel Meignant based on the book by Jeffrey Masson, "The Assault on truth, Freud's suppression of the seduction theory", Farrar edition, Strauss and Giroux, New York, 1984. It includes the exclusive interview by Jeffrey Masson, which he filmed on April 11, 2011 in Aukland, New Zealand. The new French translation of the book, with the preface by Michel Meignant, "Investigation at the Freud Archives, from real abuse to pseudo-fantasies", is available from Éditions L'Instant Present in Paris, 2012.

Image : Michel Meignant

Editing : Daniel Le Bras

Running time : 1 h 28

asclepia © 2022

National release

Wednesday, August 31 at 1pm at LE STANDRé DES ARTS - Paris 6e

CHRONOLOGY

Freud's letters to Fliess

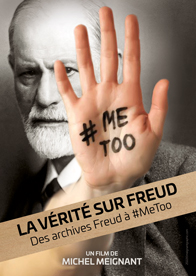

Sigmund Freud and Wilhelm Fliess

1887/1904 - Correspondence of 284 letters written by Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess

All letters written by Wilhelm Fliess to Sigmund Freud during this period have been destroyed by Sigmund Freud himself.

On December 17, 1928, Freud wrote to Ida Fliess, Wilhelm's widow, in response to her request for her husband's own letters to his friend.

"My memory tells me that I destroyed most of our correspondence at some time after 1904. But it's not out of the question that some of these letters, after methodical research, may have been preserved and reappear after a search of the room where I've lived for the last thirty-seven years. Please give me some time until Christmas. Anything I find will be at your disposal unconditionally. If I don't find anything, you'll have to accept that nothing escaped destruction. Naturally, I would be happy to know that the letters I wrote to your husband, who was my closest friend for so many years, will have the good fortune to be in your hands, which will protect them from any future use. I remain sincerely yours."

Authentic handwritten letter preserved in the Hebrew University Library in Jerusalem.

1950 - Publication in 1950 of 168 letters out of 284 in English under the title:

1950 - Publication in 1950 of 168 letters out of 284 in English under the title:

THE ORIGINS OF PSYCHOANALYSIS: LETTERS TO WILHELM FLIESS, DRAFT AND NOTES: 1887/1902.

(Imago Publishing, London, 1950).

This first edition was prepared by Marie Bonaparte, Anna Freud and Ernst Kris, who were responsible for selecting the surviving letters and redacting some of them

1950 - Publication in German AUS DEN ANFÄNGEN DER PSYCHOANALYSE.

FROM THE BEGINNING OF PSYCHOANALYSIS

1956 – Published in Paris in French under the title

1956 – Published in Paris in French under the title

LA NAISSANCE DE LA PSYCHANALYSE

at PUF

six years later.

1985 - Jeffrey Masson persuaded Freud's daughter Anna Freud to allow him to publish all Freud's letters to Fliess.

1985 - Jeffrey Masson persuaded Freud's daughter Anna Freud to allow him to publish all Freud's letters to Fliess.

SIGMUND FREUD, LETTers to WILHEM FLESS 1887/1904

English editions 1985, Harvard U.S.A., London, U.K.

German edition 1986, S. Fischer Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt am Main

SIGMUND FREUD LETTers to WILHELM FLIESS 1887/1904

French translation and edition only published in Paris by PUF

TWENTY YEARS LATER IN 2006.

1985 - Jeffrey Masson publishes in English

1985 - Jeffrey Masson publishes in English

THE ASSAULT ON TRUTH.

1984 - Publication of the French translation in Paris (éditions Aubier) under the title:

1984 - Publication of the French translation in Paris (éditions Aubier) under the title:

LE RÉEL ESCAMOTÉ, Freud's renunciation of the theory of seduction. .

Limited edition of 600 copies, rapidly sold out. From that date onwards, the letters could not be found in France.

2006 – Finally translated into French and published in Paris (by PUF), the complete set of LETTERS FROM SIGMUND FREUD TO WILHELM FLIESS - 1887/1904.

2006 – Finally translated into French and published in Paris (by PUF), the complete set of LETTERS FROM SIGMUND FREUD TO WILHELM FLIESS - 1887/1904.

TWENTY YEARS LATER than the German edition in Germany and the English edition in Great Britain and the U.S.A.

2011/2012 - Michel Meignant's first film :

2011/2012 - Michel Meignant's first film :

THE FREUD CASE.

Documentary 1h11, Asclépia

which in 2012 generated a new French translation of Jeffrey Masson's book:

INVESTIGATION IN THE FREUD ARCHIVES, FROM REAL ABUSES TO PSEUDO-FANTASMS. Published in Paris by l'Instant Présent.

2022 - Second film by Michel Meignant

2022 - Second film by Michel Meignant

THE TRUTH ABOUT FREUD, FROM THE FREUD ARCHIVES TO #METOO.

Documentary 1h28, Asclépia.

FOREWORD

by Docteur Michel Meignant

How I discovered Jeffrey Masson

Masson's book, The Assault on Truth, published in 1984, was widely acclaimed throughout the world, except in France, where it was roundly rejected. With only a few hundred copies printed, it is now completely out of print. For me to realize the importance of this work, I had to hear the American psychologist Andrew Leeds tell me that Sigmund Freud was more interested in his career, fame and money than in the truth. To my astonishment, he advised me to read Jeffrey Masson's book "The Assault on Truth". I discovered a copy of his French translation, "Le réel escamoté" (the title of the book in 1984, published by Aubier). At the time, I was making a film about ordinary educational violence called "Love and Punishment", and I was very surprised to see that psychoanalysts often refuse to take into account the reality of childhood and adolescent trauma.

Reading Masson's book, I discover that Freud initially believed in trauma theory (seduction theory) and replaced it with drive theory and the Oedipus complex. Because of his father's death, and perhaps for reasons of professional opportunism. What a great subject for a film! I meet up with Jeffrey Masson, who lives in New Zealand. I'm off to interview him for the film "The Freud Affair" (see www.l-affaire-freud.com) and on my return, I'm looking for a new publisher to reissue Jeffrey Masson's book. Here it is, in a larger translation: Investigation at the Freud Archives..

Andrew Leeds

The secret archives of psychoanalysis

It's common practice to keep documents secret in the military or political spheres, in order to preserve a nation's security and independence. But who could have expected documents classified as "secret" to exist in the field of psychoanalysis? What secrets are we trying to preserve? Where is the danger? Who benefits from censorship?

The secret this book is about is the circumstances surrounding Freud's discovery of a theory that took trauma into account, known as the "theory of seduction", and the reasons for abandoning it in favor of the "theory of drives", which were the subject of an attempt at concealment. The development of the seduction theory and its abandonment in favor of the drive theory, accompanied by the invention of the Oedipus complex, can be traced in great detail through Sigmund Freud's own correspondence with Wilhelm Fliess, which lasted 17 years, from 1887 to 1902.

To keep the story of this elaboration and abandonment secret, it was obviously necessary to destroy all correspondence that might reveal the detailed circumstances of this affair. This correspondence consisted of 284 letters from Freud to Fliess and probably as many from Fliess to Freud. To preserve secrecy, Freud burned all the letters he had received from Fliess. As for his own, which were in the hands of Ida Fliess, his friend's widow, Freud could only hope all his life that they would not fall into the wrong hands.

The divan

An incredible combination of circumstances exposes the secret

Unbelievable combination of circumstances exposes the secret The truth has been revealed under truly novel conditions. Freud's letters were not destroyed. They are now preserved in the Sigmund Freud Collection at the Library of Congress in Washington. When, after Wilhelm Fliess's death, his widow Ida Fliess wrote to Freud asking for the return of her husband's letters, he replied that he had burned them. She concluded that her husband's letters must never come into Freud's hands, because she imagined he would destroy them. In 1937, Ida Fliess sold the letters through the Viennese bookseller Reinhold Stahl to Marie Bonaparte, Princess of Greece, who was at the time in analysis with Freud. Ida Fliess asked him to promise that the letters would never fall into Freud's hands. The letters were then the object of some incredible twists and turns.

After refusing to sell them back to Sigmund Freud, with whom she was in psychoanalysis, Marie Bonaparte decided to deposit them in her safe at the Rothschild Bank in Vienna during the winter of 1937-1938. When Hitler invaded Austria, the bank was no longer a safe haven. Using her diplomatic immunity as Princess of Greece, Marie Bonaparte managed to remove these precious documents from her safe in the presence of the Gestapo. In February 1941, Marie Bonaparte, who had taken refuge in Paris, deposited the documents with the Danish legation. At the Liberation, she found the letters intact and took them to London, wrapped in waterproof and buoyant material, in case of a possible shipwreck while crossing the English Channel. The letters were then published in 1950 in a version purged of everything to do with the theory of seduction.

Jeffrey Masson was instrumental in bringing this cover-up to light. He has transformed himself into an investigative psychoanalyst, a man of courage and integrity who will reveal the truth at his own expense. At first, he had no idea that his revelations would cause a scandal. On the contrary, he thinks that all psychoanalysts will be interested. His colleagues were not at all concerned about the content of these letters, but only vehemently reproached him for betraying "the secret". It was nobody's business, and was never to be revealed. Psychoanalysts would make Jeffrey Masson pay dearly for this. At the time, he was a temporary archivist on a fixed-term contract for one year, with the promise of permanent tenure if he performed satisfactorily. But he was dismissed sine die and put out of work without compensation. He was forced to take legal action to obtain compensation of one year's salary.

Even more "infamous": to officially practice as a psychoanalyst, he had to be a member of the International Society of Psychoanalysis. He was immediately disbarred, which meant he could no longer practice psychoanalysis. This did not prevent him from publishing the entire Freud/Fliess correspondence and, above all, this book, which reveals all the ins and outs of the affair. Let's not forget that there are still secret documents, which no one has ever read, on deposit in Washington. They are censored until 2060. In the meantime, here's the story of Sigmund Freud's letters to Wilhelm Fliess. This book may make you want to read the entire correspondence, published in the U.S. and London in 1985, and in French in Paris only in 2006, more than 20 years later, by Presses Universitaires de France. The French translation of the expurgated version took only four years. At last, everyone can make up their own minds. The truth is out.

What does this mean for psychotherapists?

As in all the sciences, respect for the truth and the accurate publication of work is a matter of the most obvious ethics, in the interests of the advancement of knowledge. The subject of the secrecy we wanted to preserve is of the utmost importance, since it concerns the birth and foundations of psychoanalysis. The controversy concerns the way in which psychoanalysts welcome the revelation of trauma during treatment. It's a question of taking a stand on this revelation.

Is this the story of a real event, or just a figment of the imagination? A growing number of today's therapists attach great importance to the damaging effects of trauma. For her part, Anna Freud, Sigmund Freud's daughter and spiritual heir, believed that if this secret had been revealed, there might not have been any psychoanalysis. What do you think, as a therapist like me? Are you, like Jeffrey Masson and myself, convinced of the importance of real trauma? Do you think, like Ferenczi, that psychoanalysis free of drive theory is possible? More effective? Rid of its toxicity? Rethinking our therapeutic practice without the model of drive theory requires a highly-developed sense of vigilance and critical thinking, given the extent to which this misogynistic, paternalistic theory (in the image of turn-of-the-last-century culture) has found its way into every aspect of our lives: taught to final-year philosophy students, to doctors, psychologists and in many schools of psychotherapy that do not claim to be psychoanalytical, it is over-represented in popular culture. Its influence is still strong, especially in France, as it has contaminated the way we understand child psychology.

The theory of impulses prevents us from hoping that Jeremy Rifkin's homo empathicus will save the earth and humanity. If, like more and more therapists, thinkers and journalists, you've always been circumspect and dubious about drive theory, but found it difficult to criticize it, or worse, to cast doubt on what has for so long been presented as a truth that only the feeble-minded could understand, this book will be like a real liberation for you. You'll no longer be caught in the rhetorical trap of the circular reasoning practiced by so many analysts: "If you don't believe in the relevance of the drive theory, it's because you're unconsciously resisting this revelation, which proves just how right this theory is".

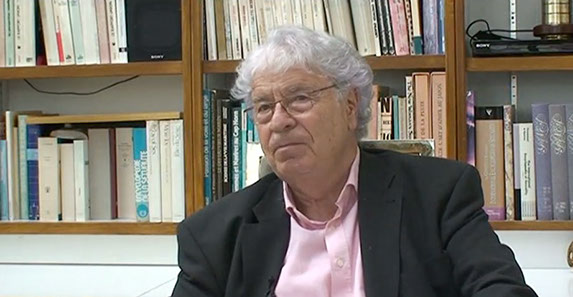

Doctor Michel Meignant

Psychotherapist and filmmaker

Honorary President of the French Federation of Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis (FF2P)

Paris, 2012

... And the #MeToo movement...

By Michel Meignant

The problem was believing women when they complained.

It was very easy: a woman complained, she made it up, she had an Oedipus complex. As a result, she was prosecuted for making false statements and even ordered to pay damages to the man who had raped her.

The abuse of women was widespread, particularly in an environment like show business, cinema, theater, television... To get a role or a good position in a department store, when the head of the department (perfume, for example) wanted to rape, or have sexual relations with a salesgirl, he would put her in drafts [we see Michel laughing], or make remarks that would prevent her from getting a promotion. And so, the rape of women, the incredible abuse continued.

On October 5, 2017, the New York Times published an article by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey that would change the world. Investigating disturbing allegations, the two journalists had, for months, secretly met and persuaded Harvey Weinstein's victims to testify. Actresses, former employees of the producer, celebrities and unknowns, many women who had previously kept silent spoke out around the world. This book is the breathtaking account of the investigation that ignited the #MeToo movement on a global scale.

The fundamental thing that changed everything with the #MeToo movement was that people believed them.

They were finally allowed to speak out...

For me, Metoo is a method of group psychotherapy: daring to speak out in a group and being supported by other people who are saying the same thing has a real therapeutic effect.

But of course, this means abandoning the theory of drives and returning to the theory of seduction.

Which really makes Freud look brilliant. How could he have made this discovery in the first place? He really had to be brilliant. And what a pity he changed his mind.

FOREWORD

by Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson

to the new French edition of:

The Assault on Truth Enquête aux Archives Freud

L’instant présent Editions, 2012

For years, doctors, psychiatrists, therapists and even legislators failed, for a variety of reasons, to recognize the extent of child abuse, ranging from simple spanking (which I'm glad to see is now illegal, even in the domestic sphere, in many countries) to crimes such as child pornography, beating and torture. All this has changed, and there are fewer and fewer people who refuse to see the impact and importance of this subject, particularly among those whose job it is to help children overcome this legacy of violence. There's no longer any room for debate.

Unfortunately, this is still not the case when it comes to the other form of child abuse - sexual assault. For complex reasons, therapists of various schools still persist in minimizing the impact of sexual abuse on children's psychological development. While some nations have been willing to acknowledge the prevalence and after-effects of sexual abuse, this is unfortunately not yet the case in France.

A case in point: the late Jean Laplanche, a particularly renowned psychoanalyst, believed that "seduction" (the sexual abuse of children) was something quite different from what Freud believed, what I believed, or even what Lacan believed (trauma is symbolic - but symbolic of what?). According to him, "seduction" is above all a message from the adult to the child. Laplanche asserts that it's a universal phenomenon. He writes: "There is something unconscious that the most violent or perverse adult addresses to the other, even in his most brutal acts. This address, or message, is therefore a universal category, much broader than the factual category of physical or sexual aggression. Not all seductions are abuse." Although his discourse is rather obscure, its consequences are alarming.

Laplanche continues, this time about my book: "Masson, for example, limits himself to factual seduction. I'm always amused by the subtitle of his book, 'Freud suppresses the theory of seduction', because it shows that Masson has understood absolutely nothing about this theory".

It's fair to say that I think "seduction" is sexual abuse, a real act in a real world. Freud thought so too, for a while, before changing his mind. Freud came to believe that these memories were just fantasies, or even memories of fantasies. Not only does Laplanche think I'm wrong to disagree with Freud, he also thinks Freud was wrong and didn't understand the true meaning of abuse: "Freud never imagined that there could be categories other than factual reality and imagination... Freud was obsessed with the concept of the real scene."

I agree with him that Freud was obsessed with the notion of reality. And that's a credit to him. I even think he continued to be interested in real abuse right up until his death, because I found a whole series of letters in his London office relating to child abuse and the Ferenczi affair. No one really understood why Freud had kept these letters in his personal desk drawer for so many years. I think it's possible that Freud felt guilty about abandoning his patients in the past. I could be wrong.

But I don't think Freud could have believed, as Laplanche (and his many followers in France) did, that sexual abuse is simply a message from the unconscious to the "other". In effect, this would mean that there is no real child abuse, just messages. And messages can be misinterpreted. It's a convenient belief for sexual predators and those who rely on denial. But it's a serious mistake, one that therapists should carefully avoid. No therapist, no matter which school trained him or her, can afford to ignore child sexual abuse any more than he or she can ignore physical abuse.

First of all, statistics on sexual assaults unambiguously demonstrate that this is a major problem in Europe, even if this information has been slow to be disseminated (Canada and the United States were pioneers in this type of research for a time). A colossal meta-analysis was published in 2011, bringing together 217 publications published between 1980 and 2009, corresponding to 9,911,748 participants. The authors conclude that child sexual abuse is "a global problem of considerable magnitude". The figures vary from publication to publication, of course, but can be as high as 50% of girls under 18 having had a sexual abuse experience. Let's not get bogged down in controversy about the definition of sexual abuse.

In fact, everyone knows exactly what it is. The Council of Europe, for example, describes it as "engaging in sexual activities with a child: by using coercion, force or threats; or by abusing a recognized position of trust, authority or influence over the child, including within the family" (Article 18, Council of Europe, Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse). The term "child" refers to any person under the age of 18, as defined in Article 1 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Incriminated sexual activities range from forced contact to sexual intercourse, including intentional exposure of the child to sexual activities.

Although I haven't found any statistics on child sexual abuse in France, the figure is probably one in four girls, based on studies carried out in other parts of Europe.

Freud was undoubtedly the first person to measure the extent of sexual abuse in society. If he became interested in this subject so early in his career, it's surely because he was one of the very first therapists to allow his patients to talk about what had happened to them. Many of them talked about sexual abuse. Not surprising, considering that he saw patients who were desperately unhappy (what he called "neurosis"). I don't think the situation would be so different today: most people who seek the help of a therapist do so because they have suffered trauma. There's no reason to suppose that the percentage of sexual assault victims among therapists' patients is lower than the percentage of victims in the general population. On the contrary, there are strong reasons to believe that the percentage is significantly higher, as we learn from an excellent series of articles published by John Read and colleagues.

Given that child sexual abuse is always an abuse of power and trust, it's not surprising that its consequences are profound and long-lasting. Few professional therapists would deny this. It is therefore imperative that all therapists, whatever their school, become aware of the importance of child sexual abuse in their practice.

I'm a lucky man. Normally, when a book goes unnoticed in a country, it doesn't get a second chance. But in my case, Dr Michel Meignant (Vice-President of the World Council for Psychotherapy and Founding President of the French Federation of Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis) read my book, and thought it deserved to be published again in French-speaking countries. He even made a film about it. We found we had something in common: our aversion to corporal punishment of children. Fabienne Cazalis, a neuroscientist, read my book when she was doing research at the University of California Los Angeles in the USA. When she saw the film, she realized how much we had in common and set about publishing a new translation of my book. She has put a lot of hard work, and even more intelligence, into this task, and I'm happy to be her friend now. It has been an honor to work with her.

It's almost thirty years since this book came out. Its main thesis is quickly summarized: I wanted to show, on the basis of new documents, and in particular unpublished letters from Freud, that the official history of Freudian thought on "seduction" (which should be called "sexual abuse", a term Freud sometimes used as a synonym for seduction), a history enshrined by Anna Freud and other seasoned analysts, is in fact erroneous. During my training as an analyst in Toronto, we were taught that Freud had initially believed that his patients, and in particular his female patients, had been sexually abused as children and that this abuse had caused their "neurosis" or "hysteria" or even "psychosis". But, we learned, Freud had realized that he had made a serious mistake, which he corrected as follows: these abuses were in fact only fantasies. I found this hard to believe. When I was certified as a psychoanalyst, I went in search of every possible document that could shed light on this fundamental subject (which no one today would call trivial). I had the good fortune to benefit from the help of Anna Freud. She generously opened the doors of Freud's house to me and allowed me to search through the cupboards and desks for all the material relating to sexual abuse. I found a veritable treasure trove, reproduced here in this book.

It was in France that I found the main clues that led me to the conclusions I propose. At the Paris morgue, I identified documents indicating that during his Parisian sojourn in 1885, Freud witnessed things that well explain his curiosity about sexual abuse. In his library, there were French books devoted to this subject, at a time when no one was interested in it anywhere in the world. In particular, there was a book by Ambroise Tardieu published in 1860, Étude médico-légale sur les sévices et mauvais traitements exercés sur des enfants, a historical document of major importance, which deserves to be recognized as such.

In London, I found a series of unpublished letters relating to Sándor Ferenczi, Freud's close friend and disciple, and sexual abuse. I'm delighted to see that France is leading the way in the rehabilitation of Ferenczi's thought, thanks to the work of one of his relatives, a fantastic French psychoanalyst, Judith Dupont. She was instrumental in the publication in French of Ferenczi's extraordinary Journal Clinique (Payot, 1985). She has also published the Freud/Ferenczi correspondence, invaluable for anyone wishing to understand the history of psychoanalysis. I'm also delighted by Pierre Sabourin's new book on Ferenczi, because he understands the importance of Ferenczi's convictions on sexual abuse, and their current significance for all clinicians.

One of the most important controversies my book has raised since its publication concerns the question of false memories. Can a person be wrongly accused of sexual abuse on the basis of a false memory? Of course, it would be absurd to claim that this never happens and that false memories don't exist. Just as it would be absurd to claim that most memories are in fact false memories. But that's what happened for years: men in the professions of psychiatrist, psychologist and psychoanalyst (as well as some of their female colleagues) claimed that women's memories couldn't be trusted, especially if they accused a man of doing things he shouldn't have done, and even more so if they accused a man in a position of power of sexual abuse. Needless to say, it was all very convenient. But it wasn't true. It was finally admitted that these allegations were primarily a means of protecting sexual predators from the legal consequences of their actions. A certain amount of resistance was organized, however, in the form of a sudden academic interest in false memories. These hotbeds of resistance are, of course, home to men accused of sexual abuse, and others who fear they may one day be. Even if the vast majority of accusations of sexual abuse are considered legitimate (as is the case with accusations of rape), the fact remains that, as with rape, there are indeed a small number of false accusations. What's surprising is that it's these few cases that tend to absorb all the media attention, partly because sensational subjects are always more interesting than routine cases, but also because it's a way of casting doubt on the accusations as a whole. Having studied the literature on the subject, I'd say that the figures for false accusations are in the region of 2-8% of cases.

If you are the victim of a false accusation, it can ruin your life. But if you're one of the 92-98% of women who have legitimately accused someone of sexual abuse, that too can ruin your life. I obviously have nothing against research on false memories per se, but I notice that it's of much lower quality than research on sexual abuse. It may be biased by a conflict of interest: men who have been accused (rightly or wrongly) want to defend themselves by putting forward studies that show these accusations to be false. Whereas women who have been sexually assaulted simply want to disappear. It took a lot of courage to tell their story. Let's not push them back into the darkness.

Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson

Auckland, New Zealand, August 2012.

Olivier Maurel

yes, human nature is good!

Spankings, slaps, caps, slaps or canings... In many countries, the most serious surveys show that over 80% of children are still subjected to violent educational methods.

Spankings, slaps, caps, slaps or canings... In many countries, the most serious surveys show that over 80% of children are still subjected to violent educational methods.

Yet, as astonishing as it may seem, no great philosopher has taken into account the consequences of this violent training, inflicted for millennia on the majority of human beings at a time when their brains are still forming, in his or her reflections on human nature.

Worse still, religions, philosophies and even today psychoanalysis all assume that the origin of human violence and cruelty lies in the very nature of children. And yet, the most recent research has revealed in them skills - attachment, empathy, imitation - that make them remarkably gifted for social life.

Does the source of human violence and cruelty lie in the nature of children, i.e. in our nature, or in the method we have always used to bring them up?

Olivier Maurel answers this question, drawing on Alice Miller's research and the most recent discoveries in neurology. After reading this ground-breaking plea, it will be difficult to continue to call hitting a child "education".

From protected child to corrected child

Humanity began to correct its children by hitting them, probably from the Neolithic period onwards. This marked a break with the behavior of hunter-gatherers, who still never hit their children anywhere in the world.

Humanity began to correct its children by hitting them, probably from the Neolithic period onwards. This marked a break with the behavior of hunter-gatherers, who still never hit their children anywhere in the world.

How did such a change occur in a field as essential as the educational relationship? Why has no one ever paid attention to this major break in human evolution and its consequences?

Reflecting on this question sheds considerable light on our past, our present and the evolution of each and every one of us.

Olivier Maurel has written several books on child abuse: La Fessée (La Plage, 2001), Oui, la nature humaine est bonne (Robert Laffont, 2009). Continuing his research, he shows here that child abuse is an unexplored anthropological question.

Bruno Clavier

THEY DIDN'T KNOW...

Why the shrink overlooked sexual violence

PAYOT Editions - 2022

Malgré l'urgence, une majorité de psys

Malgré l'urgence, une majorité de psys

ne sont pas préparés pour aider les victimes

de violences sexuelles !

Millions of people. The colossal scale of sexual violence is finally recognized by our society. What's next? Bruno Clavier is convinced that the problem lies with shrinks, who are on the front line when it comes to helping victims. Although specialized structures, associations and hotlines now exist, for over a century the vast majority of psychiatrists, psychoanalysts and psychologists have not been trained to deal with the reality of sexual violence. This is due not only to the denial of our society, but also to a theory that has denied this reality. Its author, Freud, had a secret reason for this. This secret, and the incredible therapeutic flaw that has led generations of therapists down a blind alley, preventing most of them from helping victims as they would like, are at the heart of this book. So that we never again hear the words: "It can't be done", "I didn't know".

Bruno Clavier, a psychoanalyst and clinical psychologist who himself was sexually abused as a child, is the leading exponent of transgenerational psychoanalysis. He is the author of Fantômes familiaux, which immediately became an essential reference.

back to home sunny side of the doc 2023

Michel Meignant

+33 (0)6 07 76 07 64 / +33 (0)1 47 04 37 04 / michelmeignantcabinet@gmail.com

17 ter rue du Val - 92190 MEUDON